As mentioned in the previous post about James and Fannie’s marriage and divorce, the custody court case for Camille took three weeks, 176 witnesses, and 4 days of arguments. It is a sensational story that would fit right in with today’s sensational news coverage. This story had “legs” as the old newspapermen used to say. Stories were published in newspapers from New York and Philadelphia to Los Angeles and San Francisco, from Butte to Nashville and lots of papers in between.

Fannie died at her mother’s house in St. Louis on October 9, 1886. On October 10, Mrs. McManus sent Camille to Des Moines, IA with a family friend. James filed a lawsuit on October 12 to gain custody of his daughter, claiming that she had been kidnapped and he did not know where she was.

A judge dismissed the suit on October 18 due to Camille being in Des Moines and not within the jurisdiction of St. Louis. However, there was some drama;

Albert Jackson, a colored janitor at 305 Olive street [sic], testified that a colored man named Johnson was given $10 by Mr. Gist Blair to serve the writ upon Mrs. McManus; that the witness gave Johnson the job and that Johnson afterwards reported to Mr. Blair, who duly cautioned him as to whether he was positive that he had served Mrs. McManus. His description of that lady tallied with the one given, and there was reason to believe that Johnson had served the right party, although he acknowledged that he did not know the lady personally, but had asked for her and handed the copy of the writ in at the door to a lady answering the description. Johnson could not be found to-day at the address given to Mr. Blair.

The next day, October 19, a warrant was issued for John Johnson for lying about serving the writ to Mrs. McManus. According to testimony, Mrs. McManus was in East St. Louis, IL catching a train to Des Moines at the time Mr. Johnson said he served the writ. Why she went to East St. Louis to catch a train that had to then cross the Mississippi and stop in St. Louis on its way to Des Moines was never properly explained. Later it was said that she had gone to East St. Louis to avoid being served the writ. But, whatever the reason, poor Mr. Johnson got caught in this family drama.

Frannie’s Will

On November 20, 1886, James, acting on behalf of his daughter, filed suit against Thomas McManus to set aside Fannie’s will. The suit accused Thomas of using undue pressure to make Fannie write her will just before she died and leave almost everything to him instead of Camille. At the custody hearing, Mrs. McManus testified that she planned to leave a large amount to Camille and Thomas McManus testified that if Camille was in the custody of his family, he would not only surrender all rights to the inheritance from Fannie to Camille, but add a considerable sum to increase it.

National Press Coverage

In January 1887, it looks like the Patrick and McManus parties took shots at each other through two news stories that were picked up by newspapers from one side of the country to another. Some papers ran bits of both, others chose one or the other to print.

It starts in Denver;

Denver, Col., Jan. 22 – The whereabouts of Baby Patrick, four years of age, and heiress to a million dollars, is exciting much interest in Denver. The child is the daughter of James M. Patrick of Colorado, who married the daughter of millionaire McManus of St. Louis in 1879. The wedding was one of the finest social events that ever took place in St. Louis. Mr. Patrick is a member of the St. Louis family of Patricks, who are wealthy and influential, some of the family having ranches and silver mines in Colorado. The young couple traveled in Europe, and on their return went to Bradley county, Tenn.

Soon after they returned from the continent a baby was born, and in 1884 they came to Colorado, owing to Mrs. Patrick’s failing health. Her health continuing to grow worse, Mrs. Patrick and child were sent to Canon City, where both are said to have been spirited away from the state by a friend, or relative, of the McManus family. The husband began to search and learned that they had been taken to the McManus mansion in St. Louis.

This occurred last summer and in October Mrs. Patrick died. It is asserted that before her death she made a will disinheriting the child, having been made to believe that she had been deserted by her husband. This will will be contested in the St. Louis courts, and it is said that Mr. Patrick will soon begin a suit in the courts of that city in relation to the child and her interests. The father is still making every effort to find his child. The litigation promises to be sensational.

Then the McManus response;

St. Louis, Jan. 22. [By the Associated Press.] The dispatch from Denver states that James M. Patrick, a wealthy ranchman of that city, had brought suit in the courts of this city to recover the possession of his infant child who is heir to an estate worth $1,000,000 and is supposed to have been abducted by his wife’s people, was show this morning to Ward McManus. Mr. McManus said that Mr. and Mrs. Patrick’s married life was never very happy and on account of her husband’s conduct he wife was obliged to come to St. Louis to her mother. She sued for a divorce while here. The child is now with it grandmother in Davenport, Iowa, and Patrick knows it. “It was its mother’s dying wish,” Mr. McManus said, “that her husband should never get control of it, and we shall see that that desire is complied with.”

Needless to say, there was never a million dollars at stake. Old Mr. McManus was listed in 1870 census as having about $130,000 in property, which was a nice, little fortune, but short by several hundred thousand dollars of a million. William Patrick, James’ father, had a bit more than Mr. McManus, but still short by a long way of a million. A list in the family papers, probably made by James, of Fannie’s property show that she had about $30,000 of property, jewels, and clothing in her own name. I can believe that Thomas McManus had convinced his sister that if she left all her property to him he would see that Camille received it and not James.

Lawsuit filed in Davenport, IA

After the first custody suit was dismissed in St. Louis, James filed suit in Davenport, IA in November, but it was dismissed. I haven’t found out why. Then James tried again on May 14, 1887, and this suit went forward.

The Judge’s Ruling

The Morning Democrat of Davenport, IA, printed the entire ruling of Judge Brannan. There was short editorial article printed along side the ruling that said in part, “The decision proves disappointing to one side and possibly to the side which has the largest popular sympathy or sentiment, but as to its justice there can be no question.”

In his opinion, Judge Brannan wrote:

“Family quarrels are of all other the most bitter, vicious and unrelenting; and this is especially true, when, as in this case, the subject of the controversy has it seat in the affections of each of the parties, and is bound to them by the tenderest ties. The privacy of the household is unveiled and its secrets spread before the world in their most repulsive forms. Active crimination on one part is met by counter crimination on the other and things are said and done which are rarely forgotten and seldom forgiven.”

The Case for the McManus Family

Fannie wanted her daughter brought up in a loving home and did not think that James and his parents would give Camille that kind of home. During the trial it was revealed that Fannie had a ‘violent dislike” for James’ father, William, and that she didn’t consider his mother, Eliza, very “domestic.”

In the months leading up to her death, Fannie tried to get her married sister, Mrs. Wolcott, to accept guardianship of Camille, but her sister declined. Fannie then wanted her mother to take Camille. According to testimony, Fannie filed for divorce in order to get sole custody of Camille so she could thereby be able to determine who would care for Camille after her death.

The McManus family also tried to show that James was unfit to care for his daughter. They brought up the fact that he had been indicted for embezzlement of the St. Louis City Treasurer’s office. However, subsequent examination of the books revealed that “every dollar of money coming into the hands of the treasurer was properly accounted for….”

Then there was the charge in Cleveland, but Judge Brannan didn’t give this much weight since James had gone to Cleveland to answer the charge and had posted bond. At the time of the custody trial, the matter was still up in the air, but the Judge didn’t think it had any bearing on James claim to custody of Camille.

The Judge also went through incidents that the McManus family had put forward as proof of James’ neglect and abuse. Mostly it sounded like James lacked empathy for his wife and expected her to be stronger and healthier than she was. He wanted her out and about, getting fresh air. He tried giving her medications according to his views rather than her doctors’ instructions. It could be argued that he cared for her the best he could but was ignorant of what would actually help her. It could also have been a case of gaslighting and abuse. It is difficult at this remove to tell.

The Case for James

James was Camille’s father. That was the insurmountable bar that the McManuses had to clear and were not able to.

They were not able to show that James had physically or emotionally abused Camille. He had shown his love and desire for Camille to live with him ever since she was taken from Colorado.

In his opinion, Judge Brannan went through all the arguments against James, but found that none of them was serious enough to cut the bond.

“The parent is bound to his child by the strongest ties of natural affection, and the law looks upon the parent as the one who has not only the deepest interest in it, but the one who of all others will be most likely to guard and promote its welfare by his care of it when it is young and his counsel when in its more advanced years.”

He continued on through other arguments. The parts I thought most interesting are:

• Much as there may be in the conduct of the father to reprehend, it is not claimed that he is a man of loose morals or bad habits. There is therefore nothing to show that the morals of the child would be tainted or it nature perverted by association with him.

• He has at least a home for it with his parents and they are persons of excellent standing and highly spoken of in St. Louis, where they lived for over 40 years.

• Mrs. Eliza Patrick, his mother, may not be a woman of the strong domestic nature and the deep motherly instincts of Mrs. McManus, but she is a woman of superior and well-cultivated intellect, of refinement, of good judgement….I cannot say that under her tutelage the child would be in any danger.

• This is not a contest in any sense between the two grandmothers. If that were all, and the rights of the father were wholly out of the way, under the facts in this case, the duty of the court would be plain, and no court would long hesitate to leave the child with Mrs. McManus.

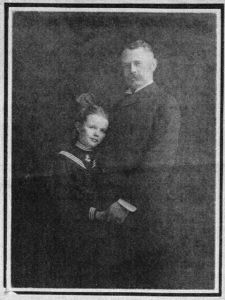

James and Camille Patrick

Controlling and Decisive

Several times in his opinion, Judge Brannan mentions the superior claim a parent has on their child, but it is clear in his opinion, that he would prefer to give custody to Mrs. McManus instead of James.

“There is another matter which has a most important, and it may be added a controlling bearing on this case, which, unpleasant as it may be to refer to, cannot be overlooked or underrated. Mrs. McManus is in her 64th year, and it will be but a few years before she reaches what is regarded as the ordinary limit of human life.” Then he goes on to point out that Camille might form “attachments, relations, and associations from which it might be hard to separate it” in her grandmother’s household. So it would be best for the child to go to her father now, and not suffer the pain of separation that would occur after Mrs. McManus’ death. “This, in my judgment is decisive of the case.”

Brannan starts to wrap up his decision with:

“I have given to this case the deepest and most anxious thought, and whatever my own personal wishes and desires may be, my duty, painful as it is, under the law, as I am constrained to view it, leave me no other alternative than to order that the child be returned to its natural guardian, the father.”

One thing that jumped out at me in his decision, Judge Brannan wrote that Iowa state law gave equal custody of children to the father and mother, where as Colorado law gave custody of children to their father. It would also explain Fannie’s desire to divorce James so quickly. If she had established legal sole custody to Camille before her death, she could decide where Camille should go. Colorado gave James the upper hand in custody cases. I don’t know what Missouri was like at the time, but if the McManus Family felt it best to get Camille out of the state as fast as possible, I would guess that Missouri law was closer to Colorado law and Iowa law. Otherwise, there is no reason for Camille to be shipped off so quickly.

After the Decision

Camille went to live with James in Denver. Unfortunately, less than three years later, in January 1890, she came down with diphtheria and died. I wonder how long Camille would have lived if she had been living with her McManus grandmother. Would she have succumbed to diphtheria or some other disease in St. Louis? As for the “controlling and decisive” concern about Mrs. McManus’ age, she lived another 19 years, finally passing away in 1905. She outlived both of her co-grandparents, Eliza and William Patrick. Camille would have been 22 and probably would have been able to deal with the pain of separation.

Gentile Poverty of the Patrick Family

Aside from the emotional toll of James’ failed marriage, his personal problems also helped reduce his entire family to gentile poverty. Mining probably took a good share of the family wealth, but legal bills certainly ate up whatever was left.

During all of the moving about that James and Fannie did in the last years of her life, a letter from Annie to James fell into the hands of Ward McManus. McManus gave this letter to Frank Bowman who then filed a lawsuit against James and Will. That suit continued until 1893 and drained Will of all his money.

William and Eliza supported James and contributed a great deal of money toward the costs of the custody battle and trying to break Fannie’s will. One of James’ nephews, Phil Eddy, wrote some remembrances in the mid-1960s. He wrote about how well his mother, Clara, had handled the family’s gentile poverty. She had grown up privileged in a house with several servants, but the money William and Eliza had spent on James’ legal bills caused them to live with Clara and her family and not contribute much to the household expenses.

The Saddest Ending

After all the personal and courtroom drama, it was very sad to discover that not one of the concerned family members could buy Camille a headstone. She is buried in Riverside Cemetery, on the north side of Denver, in an unmarked grave. There is no reason to believe the McManuses knew about the unmarked grave. This has to be laid strictly at the Patrick family doorstep.