James Patten Brownlow was youngest son and the third of seven children of William G. Brownlow and his wife, Eliza O’Brien Brownlow. When the Civil War broke out, James and his elder brother, John Bell Brownlow, joined the northern forces to fight against the Confederacy.

As you will read, James was an outstanding leader and while only a colonel at the time of this raid in July 1864, he had attained the rank of brevet general by the end of the war.

From: History of the First Regiment of Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry in the Great War of the Rebellion by W. R. Carter.

James Patten Brownlow

Page 169

It was while McCook’s division was holding this part of the Union line that the First Tennessee, under Colonel Brownlow, performed one of the most daring and characteristic feats of the war. Colonel Brownlow was ordered to a point on tile river supposed to be fordable, with orders to cross and develop the strength of the enemy on the opposite side. The place where he was ordered to cross was at Cochran’s Ford, some little distance above the mouth of Soap Creek and near Powers’ Ferry. Whether the order emanated from General Sherman, the corps, division or brigade commander was a subject that was “cussed and discussed” by the boys, both during and after the execution of the order, and the conclusion was reached that the “General” who is- sued it must have considered the men of the First Tennessee not only web-footed but thick-skinned fellows, capable of swimming a river which they or their horses could not ford, and of going into battle minus clothing or even wearing the proverbial undress uniform of a Georgia major–“a paper collar and a pair of spurs.”

They arrived at the designated point about 3 o’clock in the morning, while the rain was falling in torrents, and at daylight discovered a small force of the enemy on the other side, supposed to number twenty-five or thirty men, who had the advantage of being on higher ground and protected by trees and rocks. As most of the regiment was deployed along the river and were busily engaged in sending their leaden compliments across, a few of the men charged into the stream without the slightest knowledge of its depth, the condition of its bed or the course of the ford.

As they advanced under a brisk fire, the water getting deeper and deeper, the boulders on the bottom getting bigger, men and horses floundering and wallowing, the bullets sip, sipping and pattering in the water, it became evident that it was not a proper place for good cavalrymen to cross, and they came back out of that river tolerably fast—at least, much faster than they went in. Though their spirits and ardor as well as their clothing and ammunition were some-

p.170

what dampened in their futile attempt to cross, they had no idea it would be the last of it, or that they would permit such an insignificant force to hold them longer in check.

A consultation of the officers was held, and it was decided to find a native who knew the ford and to show its course. Meanwhile their carbines were kept busy, and as the day wore on, Colonel Dorr, commanding the brigade, made his appearance and seemed as mad as a hornet because the boys were not in possession of the opposite side. Dissatisfied with explanations made, he gave Brownlow preemptory orders to move at once on the enemy, and uttering an unnecessary threat that would be executed in case his order was not promptly obeyed.

The acting brigade general rode off, leaving Rev. William G. Brownlow’s gallant son in a truly “fighting-mad” frame of mind. These were the facts as they came to the men in the ranks. Soon thereafter, a few of the boys were called to the rear—there were just nine men in all—and Colonel Brownlow said, “Boys, we are going to cross that river. It is plain we can’t ford it here, and as we have no pontoons, and can’t very well make a swimming charge, we’ll find another way or break the breeching.”

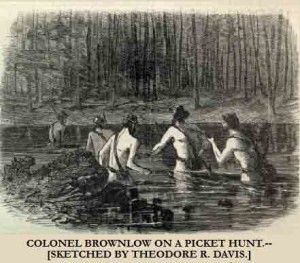

Then, giving directions for the men at the ford to keep up an incessant fire so as to divert the attention of the enemy from the move about to be made, the colonel led his little squad through the brush to a point about a mile up the river, behind a bend, where, lashing a couple of logs together and placing their carbines, cartridge-boxes and belts thereon, they stripped to the skin and, leaving their hats, boots and clothing behind, swam the river, pushing the raft in front of them.

The appearance of nine naked men with belts on, as they stood in line, was somewhat ludicrous, and while Brownlow was giving, in undertones, the directions and plan of attack, it was difficult to repress the humorous remarks interjected by the boys, witty expressions, some of them, that would make the gravest soldier laugh, but would not be appreciated

p.171

by civilians unfamiliar with military terms. “I’ll be durned if this ain’t baring our breasts to the foe, for a fact,” said one. “l reckon the rebs will climb them trees when they find out we’re a lot of East Tennessee bear hunters,” put in another. “Talk low, talk low!” said Brownlow, “for the success of this attack depends upon our quietness until we close in with the game, and then you may yell like ——.” Well, they started, with trailed carbines, into the cedar thicket, which concealed them from the enemy’s view, leaving one man to guard the raft, and moved as rapidly as the nature of the ground would permit, but the funny expressions soon gave place to some that were in violation of the Third Commandment.

They were all “tenderfoots,” and as the sharp stones and dry twigs harrowed their soles, and their naked bodies were scratched and punctured by the cedar brush and stung by insects, some vigorous profanity was naturally indulged in. ‘ ‘Curse low, men,” ordered ‘Brownlow as he turned his head, and in doing so he nearly stumbled to the ground, but as he recovered himself and went limping along he continued, in a very loud voice, “The occasion is worthy of considerable profanity, but cuss low, cuss low!” Coming to a road that led to the ford, about four hundred yards in the rear of the enemy, and reconnoitering the location and number of the rebel reserves, they formed for the charge, and moved quietly forward, unseen by the rebs, until they got within forty or fifty yards of them.

Then, turning their carbines loose and rushing on them with a yell, in a very few minutes most of those Confederates were awaiting the orders of the Tennesseans. Some of them got away, but they bagged twelve. One of the last to give up was a freckled-faced fellow, half concealed behind a tree. When he was covered and surrendered, he threw down his gun and said : “I surrender, but dog-gone my skin, Yanks, ‘taint fair to come at us in that way. If we’uns had been strong enough to take you’uns, the Confederate government ‘ud hung you all for spies, as you hain’t got no uniforms on.”

p. 172

The prisoners were hustled up the river to the raft, where they swam across in advance of their captors and were received by some of the boys, who had come up to cover the retreat, if necessary. Thus a simple little order was executed. The rebels said it was a “Yankee trick.” We’ll agree that it was. Now, you will notice, the colonel of the regiment went into that “scrimmage” just as naked as the other boys. He might have had his clothes carried across the river for him by one of the privates, or he might have detailed a lieutenant or a captain to lead the attack, while he, in some safe position, viewed the battle “from afar.” But, like a true volunteer, standing not upon his dignity or rank, he was willing to bear the same hardships or share the same fate as the privates.

General McCook makes honorable mention of this daring feat, said to be the only naked charge made during the war :

Georgia Historical Society Plague commemorating the patrol and crossing

HEADQUARTERS FIRST CAVALRY DIVISION,

DEPARTMENT of THE CUMBERLAND,

July 9th, 1864.

GENERAL: I have the honor to report that a detachment under Colonel Dorr crossed the pontoon this afternoon, and scouted the country in front of General Schofield. They found the enemy’s cavalry there in force.

Brownlow performed one of his characteristic feats to-day. I had ordered a detachment to cross at Cochran’s Ford. It was deep, and he took them over naked, nothing but guns, cartridge-boxes and hats. They drove the enemy out of their rifle-pits, captured a non- commissioned officer and three men, and the two boats on the other side. They would have got more but the rebels had the advantage in running through the bushes with clothes on. It was certainly one of the funniest sights of the war, and a very successful raid for naked men to make.

Everything is quiet along the line, and citizens on the other side say the enemy were totally unprepared for a crossing on this flank.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

E. M. McCook,

Brigadier-General Commanding Division.

The morning after this occurrence, notice was given of

p. 173

the changed situation by a reb, yelling out across the river: “Hello, Yank!” “What do you want, Johnny?” “Can’t talk to you’uns anymore.” “How is that?” “Orders to dry up.” “What for, Johnny?” “Oh, Jim Brownlow with his d—–d Tennessee Yankees swam over upon the left last night and stormed our rifle-pits naked, captured sixty of our boys and made ’em swim back with him. We’uns have got to keep you’uns on your side of the river now.” This expedition was quite successful, but it completely broke up the friendly relations that had existed the past two days between the boys in blue and gray along the banks of the Chattahoochee.

This picture is from Harper’s Weekly, Aug. 13, 1864, p. 525, along with a short story about the raid.

This picture is from Harper’s Weekly, Aug. 13, 1864, p. 525, along with a short story about the raid.

A slightly different account is given here, and is written by Col. Brownlow himself to his father.

James was shot through both thighs at the Battle of Franklin later in 1864 and did not fight again. While being treated for his injuries, he met his future wife, Belle Cliffe, the daughter of the doctor who treated him in Franklin.

Unfortunately, James suffered from the effects of his wounds for the rest of his life and died in 1879 almost a year after Belle passed away.